1890 to 1913: The life and times of

The Orange Park Normal & Industrial School

“The American Missionary Association has done noble work in the many years it has labored for the education of the downtrodden, but nothing it has done for the cause of education can eclipse its efforts against the Sheats school law, if successful” (Clay County Archives).

The Orange Park Normal & Industrial School (OPNIS) held the promise of a better life for a generation of former slaves and their children. The very short lifespan of OPNIS, the success of the school, and its reputation provided an important case of a school that accomplished the essential goal of educating the children of former slaves and offered a glance at the future of public education in Florida. The life of the school also served as a cautionary tale for future efforts of school integration, and the struggle of different Americans living and learning together.

The story of OPNIS included a brief portrait of the people that breathed life into it as they learned, taught, and administrated the work of OPNIS. Educational policies, practices, and the governing of Blacks after the Civil War provided the context for the story. Tension resulted from the American Missionary Association’s (AMA) attempt to educate Blacks and those that used the power of the state to stop that pursuit.

The result of a dangerous and unlikely arrangement for the times, OPNIS opened for service on October 7, 1891. Slavery and the Civil War had just ended and tension between Blacks and White were high. When the town agreed to partner with the AMA to build the school the terms included White children learning along side Black children (Orange Park Normal, 152-153). The town of Orange Park not only agreed to the school, but it also donated land for that purpose.

This arrangement also enjoyed, at least early on, the support of the Christian community as the Congressional Church at Orange Park’s Pastor, Reverend G. S. Dickerman, presided over exercises at the school (Orange Park Florida, 234). This bargain between the town and AMA made OPNIS one of the first integrated schools in Florida; it also meant that Black children like Carrie W. Parrott, who later became a nurse, had a chance for a bright future (Graduates of the Orange Park). After all, Just a generation earlier, Carrie’s parents and grandparent had a very different relationship with their White counterparts—instead of classmates they were masters and slaves.

Interestingly, in some writings, OPNIS bore the name “Hand School” after a philanthropist who in 1888 donated over a million dollars to the American Missionary Association. An extremely successful businessman and descendent of Puritan heritage, Mr. Hand supported the AMA’s mission and found them honest in their business. However, Mr. Hand died the same year the school opened (Mr. Hand’s Funeral, 35). OPNIS opened its doors to 26 students. This number quickly grew to 78 (Orange Park Normal, 153).

Thanks to the AMA, founded in 1946, future teachers of African American citizens learned the skills they needed as educators. Though at great risk of persecution and violence, the AMA carried on its mission in Orange Park. Due to the chances the AMA took LeRoy C. Farley attained his goal and became a teacher (Graduates of the Orange Park). If one looked at some of the pictures of the school’s operations, it is not hard to imagine LeRoy learning and playing with his fellow students completely oblivious to the danger mounting around them. OPNIS operated as a private organization even though Christian education served as one of its main objectives. During its own journey of educating future teachers of Black people, the AMA also helped to establish a number of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU’s) in states, such as Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. As a matter of fact, the AMA helped to establish over 500 houses of education for Blacks and Whites (Moon, 197).

The time and circumstances provided the opportunity for the AMA to build a school in Orange Park Florida (Orange Park Normal, 152). Orange Park needed the OPNIS as much as the AMA needed to build it. Orange Park, formed in 1876, served as a residential community for those who worked in Jacksonville, which lay about 14 miles to the north. Orange Park began as a small village made up of Northerners. Because of its supply of fresh water, fertile grounds, and beautiful landscape, Orange Park expected to grow and prosper. The town presented a beautiful and attractive place to live. According to one resident at the time, a person could walk all day in the shade of the trees (Orange Park Normal, 186). No doubt, Mercedes Gilbert who also attended OPNIS played under the canopy of those very trees (Barnes). Meanwhile, the prosperity everyone expected did not come about for a long time. Blacks and Whites struggled to make a living. While dealing with the aftermath of a plague in the late 1880’s, Orange Park did battle with harsh weather that killed dreams and hopes of a good harvest in 1894 (Blake).

When the Civil War ended in 1865, four million slaves were instantly freed. America, at great cost, had rid itself of an ugly stain on its history. While the Civil War settled one problem—slavery, all of a sudden America faced its next challenge, incorporating former slaves and their children into the fabric of this great country. This proved to be very difficult. For example, even Reconstruction, an attempt by the government to settle differences with southern states that wanted to separate themselves from the north, failed to bring freed Blacks into a peaceful existence with their White neighbors.

Amidst the backdrop of lynching and discrimination, Orange Park seemed, for a time, an oasis for the education of Blacks and their children. In fact, a strong sentiment against educating Blacks surrounded the school, which added to the conflict that started brewing as soon as the AMA and like-minded citizens in Clay County came together to establish OPNIS. After all, only a short time earlier, the southern economy revolved around slavery. Just a short distance from where the school sprang from the ground one could have seen the remnants of a plantation and its instruments of correction (The Church at Orange Park, 215-217).

OPNIS opened on 10 acres of land, on which Orange Park’s Town Hall now resides. The grounds for OPNIS stretched along Kingsley Avenue east from Smith Street to what is now U.S. 17 (then called Magnolia) (McTammany). Part of the education included agriculture, which took up some of the initial acreage. At the beginning, the campus of OPNIS saw three roomy buildings: a girls’ dormitory, one for the boys, and another for general use. The structure meant for general use owed its existence to a generous donor and bore his name—Hildreth Hall. The kitchen and dining area connected to the girls’ hall. After the school opened the builders erected another large two-story building that housed the industrial shop.

(Hildreth Hall Clay County Archives)

(Hildreth Hall Clay County Archives)

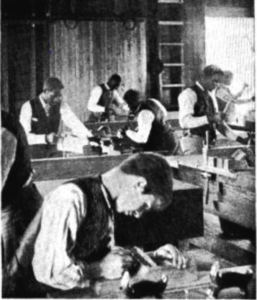

The students worked hard to get the industrial shop into shape for classes in carpentry, masonry, machine work, and architectural and mechanical drawing. Girls received training in plain and fancy sewing, millinery, and general domestic management. The curriculum encompassed grammar courses in the lower grades and so-called “normal” education in the upper year—9-12. This normal education taught the pupils how to be educators (Orange Park Normal and Manual, 187-188). Evidence of the great work done by the school came in the form of excerpts from an annual report on the school:

“… At 2 P.M. the botany class among other exercises analyzed the Spanish bayonet and passionflower, and we were forcibly impressed with the rare facilities offered for pursuing this most interesting study…. The prominent impression made on the minds of the thoughtful ones present, was the large amount of work accomplished in the eight months since the school opened. The start has been well made.” (Orange Park Florida, 234).

Part of the history of OPNIS included the AMA’s struggle to carry out its mission, especially as it relates to race relations and the integration of schools. Even while there existed an apparent need to educate former slaves, some feared what would happen if decedents of Black servants received a formal education. The conflict between those who strived for the incorporation of a newly freed people and those who feared and even resented former slaves receiving an education affected the existence of the OPNIS from its establishment to its end.

OPNIS represented, at least in part, a remedy and response to the wrong of slavery. The school also represented a recognition that a good education formed the foundation of a society, and that an educated population could contribute in a positive manner (The new south, 141-142). Meantime the prevailing sentiment—African Americans did not posses the capability of learning or the ability of contributing as productive members of the American society, hung over every effort to integrate former slaves and their decedents. However, there seemed to be an element of civility and tolerance for Blacks in Clay County leading up to the school being built.

(Industrial Room of OPNIS, Clay county Archives)

A close look at the picture “Girls washing under the pines” reveals Blacks and Whites washing clothes together. This picture reflected race relations in Clay County that appeared to rail against hatred, bigotry, and the lack of love festering off school grounds. The expressions on the young faces are not those of anguish or distress, but rather those of typical young

A close look at the picture “Girls washing under the pines” reveals Blacks and Whites washing clothes together. This picture reflected race relations in Clay County that appeared to rail against hatred, bigotry, and the lack of love festering off school grounds. The expressions on the young faces are not those of anguish or distress, but rather those of typical young

(“Girls washing under the pines” from Clay County Archives)

people getting along and going about their chores. As further illustration of the positive atmosphere that ran contrary to the building conflict, Mr. Farnham principal’s report of September 1893 said in part,

“When we looked over the large audience, the largest that our school has ever attracted, and saw there Northerner and Southerner, Yankee and Cracker, Ethiopian and Caucasian, Protestant and Romanist, American and Englishman, the learned and the ignorant, surely, we thought, the lion and the lamb have lain down together, and a little child has led them”(Clay County Archive)

What a powerful scene Mr. Farnham’s words painted. Mr. Farnham, an experienced and accomplished educator, brought an excellent group of teachers with him; they were accomplished and enjoyed excellent reputations and successes on other projects for the AMA. Thanks to the leadership of Farnham, OPNIS enjoyed praise and success. Indeed, the school’s academic reputation grew and so did its student population, at least for a short time (Clay County Archive).

While OPNIS flourished, the odds of a long and successful life began to diminish. The political climate of the time included the infamous court case of Plessy vs. Ferguson of 1896. The case involved a “Colored” man in Louisiana who in 1892 sat in the White only section of a train and was arrested. The case held that the concept of separate but equal should control the governing of the races. With this climate as context, Mr. William Sheats, Florida’s State Superintendent for Schools, took aim at OPNIS in an effort that ran counter to his job as Florida’s top educator. Mr. Sheats seemed to take personal offense at the work of OPNIS and the AMA.

While the school earned congratulations, even from foes, for its work and academics, Mr. Sheats and others conspired to close it. These same foes of OPNIS did not feel that Blacks and Whites should learn together, clinging to the wrong-headed principle of separate but equal. Thanks to Sheats’ influence on the state’s legislature, he managed to produce an edict called, “Sheats Law”(Clay County Archives). This law made it illegal for Black and White children to sit in the same classroom. In an effort to avoid Mr. Sheats’ wrath and to deflect his attention away from OPNIS, Mr. A. F. Beard (Superintendent of School for the AMA) submitted an account of the school’s operation for Mr. Sheats’ Biennial Report of the Superintendent of School. In his explanation, Mr. Beard said, in part, that, “We [the AMA] agree in the belief that such commingling of the races as now exists in the South is thoroughly wicked. We join in the purpose to create every possible influence against it” (Orange Park Normal, 188). Despite his best efforts, Mr. Beard failed to hide the fact that Blacks and Whites were being taught together. Further, Mr. Beard’s account did not prevent the fury of Mr. Sheats from coming down on the school.

The school suffered other local threats that, combined with Sheats’ efforts, made it impossible for the school to exist. For one thing, parents needed their children to help with the crops, which made consistent attendance at the school impossible. Additionally, the Ku Klux Klan harassed and threatened teachers and administrators of the school. In May of 1896, as tension and conflict mounted, the sheriff of Clay County arrested some of the staff of OPNIS, including Mrs. B. D. Rowlee; Miss Edith M. Robinson of Battle Creek, Mich.; Miss H. S. Loveland of Newark Valley, N. Y.; and Miss Margaret Ball of Orange Park, Fla. These educators were found in violation of Sheats Law. However, the AMA made arrangements to have them released (Orange Park Normal and Manual, 186-189). Soon, thereafter, the courts declared the law unconstitutional and it seemed that Mr. Sheats had failed to accomplish his goal of closing the school (Our Orange Park School, 379-380). After a losing his office in 1904, Mr. Sheats stoked the fire of hatred toward the work of OPNIS to gather support for a second term in office in 1912. The tension finally climaxed as threats against the community that once supported the school grew and another school for Whites sprang up in Green Cove. Sheats won; the school finally closed its doors.

Later, Sheats and other liked minded authorities worked to cut funding for the education of Blacks while ensuring money was available for White schools. This gave way to ill funding and discriminatory policies. And due to lack of funds and unfair treatment, Blacks and Whites experienced education differently because Black teachers and students received inferior education (Howie, 50). The schools for African American students were few and, because of the lack of teachers and funds, often went many days unopened. Even at the time of OPNIS a struggle existed between Church and State, as Sheats used the state laws to destroy OPNIS, a privately ran school that took no money from the state. The fact the state of Florida worked to oppress a private institution attested to the lengths that some people were willing to go to prevent Blacks from being educated.

While the story of OPNIS as a physical structure ended with the school’s closure in 1913, (AMA finally announced its official closing in 1918 after a suspicious fire), its influence continued. For example, some of the graduates did go on to teach and even attend medical school. The land on which the school occupied became part of the property owned by Moosehaven. It later became the first site for St. Johns Country Day School. The land that once accommodated the Orange Park Normal and Industrial School now serves as home of the Town Hall of Orange Park. The school may no longer stand, but its influence, contributions, and legacy continue.

Work Cited

“Arrest of Our Teachers in Orange Park, Florida,” The American Missionary, 50, May

1896, pp.146-147.

Barnes, Sharon L. “Gilbert, Mercedes.” American Council of Learned Societies,

Oxford UP, www.anb.org/articles/16/16-02847.html.

Blakey, Arch Frederic. Parade of memories: A History of Clay County Florida. Clay

County Bicentennial Steering Committee, 1976.

Dickerman, G.S. “Orange Park, FL.” The American Missionary, vol. 46, July 1892, pp.

234-235.

DuBois, W.E.B. “Reconstruction and its Benefits.” The American Historical Review, vol.

15, July1910, pp. 781-799.

Graduates of The Orange Park Normal School, Clay County Archives. archives.clayclerk.com/files/Black%20History%20%

20OP%20Normal%20School%20Graduates.pdf

Howie, Sheryl Marie. State Politics and the Fate of African American Public

Schooling in Florida, 1863-1900. UP of Florida, 2004. A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Education University of Florida

Jewell, Joseph O. “Education For Liberation: The American Missionary Association And

African Americans, 1890 To The Civil Rights Movement.” Church History, vol. 79, no. 4, 2010, pp. 964-967. Academic Search Complete. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

McTammany, Mary Jo, “Normal School Educated Former Slaves,” Jacksonville.com,

The Florida Times Union, 21April 2004, jacksonville.com/tu-online/stories/ 042104/nec_15387491.shtml#.WDRMAhIrK8o.

Moon, Fletcher F. “American Missionary Association (Est. 1846).” Freedom Facts and

Firsts: 400 Years of the African American Civil Rights Experience, edited by Jessica Carney Smith, and LindaT. Wynn, Visible Ink Press, 2009, p 197.

“Mr. Hand’s Funeral.” The American Missionary, vol. 46, February

1892, p. 35.

“Orange Park Florida.” The American Missionary, vol. 46 July 1892, p. 234.

Orange Park Hand School Source Documents. 2011, Clay County Archive.

“Orange Park Normal and Industrial School.” The American Missionary, vol. 46, May

1892, pp. 152-153.

“Orange Park Normal School and the Florida Persecution.” The American Missionary,

vol. 50 Dec 1896, p. 379

Sheats, William. “Orange Park Normal and Manual Training School.” Biennial Report of

Superintendent of School, June 1896, pp. 186-189.

“Our Orange Park School and the Florida Persecution.” The American Missionary, vol.

50, Dec 1896, pp. 379-380.

Richardson, Joe, “The Nest of Vile Fanatics: William N. Sheats and the Orange Park

School.” Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 64, April 1986, pp. 393-406.

“The Church at Orange Park.” The American Missionary Association, vol. 50, July 1896,

- 215-217.

“The New South and the Old South.” American Missionary Association, vol. 46, May

1892, pp. 141-142.

Town History. Found at http://www.townoforangepark.com/town-government/town

history